Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSS Act Report

Uploaded by

Alexandra Nicole Manigos Baring0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views17 pagesEmployee, Employer

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEmployee, Employer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views17 pagesSSS Act Report

Uploaded by

Alexandra Nicole Manigos BaringEmployee, Employer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 17

Employer (Section 8 [c])

Any person, natural or juridical, domestic or foreign, who carries

on in the Philippines any trade, business, industry, undertaking, or

activity of any kind and uses the services of another person who is

under his orders as regards the employment, except the

Government and any of its political subdivisions, branches or

instrumentalities, including corporations owned or controlled by

the Government: Provided, That a self-employed person shall be

both employee and employer at the same time.

SSC , et al vs. Alba

Apolonio Lamboso alleged that he worked in Hda.

La Roca (owned by Far Alba) from 1960 to 1973 as cabo,

in Hda. Alibasao from 1973 to 1979 as overseer and

in Hda. Kamandag from 1979 to 1984; that the latter two (2)

haciendas are both owned by Ramon S. Benedicto. When he

filed a claim for retirement pension benefit with the SSS,

however, the same was denied on the ground that he had 39

monthly contributions to his credit.

Lamboso averred that he received from Far Alba a

monthly salary of P45.00 from 1960 to 1965 and P180.00 from

1965 to 1973 and from employer Ramon S. Benedicto, a

monthly salary of P500.00 from 1973 to 1984; and that he was

reported to the SSS for coverage in 1973 and only a total of 39

monthly contributions were remitted in his name.

In its Position Paper, public respondent SSS avers that Apolonio Lamboso was

reported for SS coverage, effective April 1, 1970 by employer Far Alba (ID No. 07-

0869300) on December 11, 1972; that he was, likewise, reported for [SSS] coverage

effective May 1, 1980, by employer Kamandag Agri & Dev. Corp. (ID No. 07-2024250-4)

on September 1, 1980; and that Apolonio Lamboso has only 39 monthly contributions

(remitted in his favor by Far Alba) for the period January 1970 to March 1973, but

none under Kamandag Agri[.] Dev. Corp.

In the testimonial evidence for the petitioner presented on March 17 and June

15, 1999 and August 10, 2000, witnesses collectively corroborated the petitioners

employment with Far Alba from 1960 to April 1973 in Hda. La Roca and with employer

Ramon Benedicto inHdas. Alibasao and Kamandag from 1973 to 1984.

The failure on the part of respondent Far Alba to file his responsive pleading to

the petition filed by petitioner Apolonio Lamboso strongly indicates lack or absence of

evidence, by way of rebuttal, to the positive assertion of the petitioner regarding his

employment with the former from 1960 to April 1973. Besides, defrauding

respondent Far Alba reported Apolonio Lamboso to the SSS for coverage

effective April 1, 1970 and this act of reporting is already an incontrovertible proof of

employment.

Social Security Commission ruled in favor of Lamboso.

Court of Appeals:

The Court of Appeals reversed and set aside both the resolution and the order of the

Commission. It held that Far Alba cannot be considered as an employer of Lamboso prior to

1970 because as administrator of the family-owned hacienda, he is not an employer under

Section 8(c) of the Social Security Act of 1954 who carries on a trade or business, industry,

undertaking or activity of any kind and uses the services of another person who is under his

orders as regards the employment, unlike under Article 212(e) of the Labor Code which

defines an employer as, among others, any person acting directly or indirectly in the

interest of the employer. As such, the appellate court declared, Far Alba had no obligation

to remit to SSS the monthly contributions of Lamboso prior to 1970. It also held that

inasmuch as Far Alba had duly remitted Lambosos monthly contributions to the SSS for the

period of January 1970 to March 1973, which totaled 39 contributions, he

as Lambosos employer should be absolved from the adjudged liability.

Far Alba stresses that he was not Lambosos employer prior to 1970 and that he

neither had been the administrator of the hacienda because in 1960, he was

in Manila studying law and was in fact admitted into the practice of the law the following

year.

[18]

He agrees with the ruling of the Court of Appeals that the claim for the payment of

SS contributions should have been filed before the estate proceedings of Arturo Alba, Sr .

Evidently, Far Alba had indeed served

as Lambosos employer from 1965 to 1970 or, at

the very least, he had served as

the haciendas administrator before 1970. Now,

the question is whether an administrator could

be considered an employer within the scope of

the Social Security Act of 1954.

SC answered in the affirmative.

First, the Court observes that Far Alba was no ordinary

administrator. He was no less than the son of the haciendas owner

and as such he was an owner-in-waiting prior to his fathers death. He

was a member of the owners family assigned to actively manage the

operations of the hacienda. As he stood to benefit from

the haciendas successful operation, he ineluctably took his job and his

fathers wishes to heart. As emphasized by the Commission his and

the owners interests in the business were plainly and inextricably

linked by filial bond. He more than just acted in the interests of his

father as employer, and could himself pass off as the employer, the

one carrying on the undertaking.

Second, nomenclature aside, Far Alba was not merely an

administrator of the hacienda. Applying the control test

which is used to determine the existence of employer-employee

relationship for purposes of compulsory coverage under the SSS law,

Far Alba is technically Lambosos employer.

The essential elements of an employer-employee relationship

are: (a) the selection and engagement of the employee; (b) the

payment of wages; (c) the power of dismissal; and (d) the power of

control with regard to the means and methods by which the work is

to be accomplished, with the power of control being the most

determinative factor.

Lamboso testified that he was selected and his services were

engaged by Far Alba himself. Corollarily, Far Alba held the prerogative

of terminating Lambosos employment. Lamboso also testified in a

direct manner that he had been paid his wages by Far Alba. This

testimony was seconded by Lambosos co-worker, Rodolfo Sales. Anent

the power of control with regard to the work of the employee, the

element refers merely to the existence of the power and not the actual

exercise thereof. It is not essential for the employer to actually

supervise the performance of duties of the employee; it is sufficient

that the former has a right to wield the power.

Third, not to be forgotten is the definition of an employer under Article

167(f) of the Labor Code which deals with employees compensation and

state insurance fund. The said provision of the law defines an employer as

any person, natural or juridical, employing the services of the employee. It

also defines a person as any individual, partnership, firm, association, trust,

corporation or legal representative thereof. Plainly, Far Alba, as the hacienda

administrator, acts as the legal representative of the employer and is thus an

employer within the meaning of the law liable to pay the SS contributions.

Finally, the Court believes that Section 8(c) of the Social Security Act of

1954 is broad enough to include those persons acting directly or indirectly in

the interest of the employer. As pointed out by the Court of Appeals, that the

said provision does not contain the definitive phrase contained in Article

212(e) of the Labor Code should not be taken to mean that administrators

such as Far Alba, whose interests are closely linked with his father-employer,

do not come within the purview of the law. If under Article 212(e), persons

acting in the interest of the employer, directly or indirectly, are obliged to

follow the government labor relations policy, it could be reasonably

concluded that such persons may likewise be held liable for the remittance of

SS contributions which is an obligation created by law and an is employees

right protected by law.

Employee (Section 8 [d])

Any person who performs services for an employer in which

either or both mental or physical efforts are used and who

receives compensation for such services, where there is an

employer-employee relationship: Provided, That a self-

employed person shall be both employee and employer at

the same time.

SSS vs. CA, et al.

In a petition before the Social Security Commission, Margarita Tana,

widow of the late Ignacio Tana, Sr., alleged that her husband was, before his

demise, an employee of Conchita Ayalde as a farmhand in the two (2)

sugarcane plantations she owned (known as Hda. No. Audit B-70 located in

Pontevedra, La Carlota City) and leased from the University of the Philippines

(known as Hda. Audit B-15-M situated in La Granja, La Carlota City). She

further alleged that Tana worked continuously six (6) days a week, four (4)

weeks a month, and for twelve (12) months every year between January 1961

to April 1979. For his labor, Tana allegedly received a regular salary according

to the minimum wage prevailing at the time. She further alleged that

throughout the given period, social security contributions, as well as

medicare and employees compensation premiums were deducted from

Tanas wages. It was only after his death that Margarita discovered that Tana

was never reported for coverage, nor were his contributions/premiums

remitted to the Social Security System (SSS). Consequently, she was deprived

of the burial grant and pension benefits accruing to the heirs of Tana had he

been reported for coverage.

The SSS, in a petition-in-intervention, revealed that neither Hda. B-

70 nor respondents Ayalde and Maghari were registered members-

employers of the SSS, and consequently, Ignacio Tana, Sr. was never

registered as a member-employee.

Respondent Ayalde belied the allegation that Ignacio Tana, Sr. was

never her employee, admitting only that he was hired intermittently as

an independent contractor to plow, harrow, or burrow Hda. No. Audit

B-15-M. Tana used his own carabao and other implements, and he

followed his own schedule of work hours. Ayalde further alleged that

she never exercised control over the manner by which Tana performed

his work as an independent contractor. Moreover, Ayalde averred that

way back in 1971, the University of the Philippines had already

terminated the lease over Hda. B-15-M and she had since surrendered

possession thereof to the University of the Philippines. Consequently,

Ignacio Tana, Sr. was no longer hired to work thereon starting in crop

year 1971-72, while he was never contracted to work in Hda. No. Audit

B-70.

Commission finds that the late Ignacio Tana was employed by

respondent Conchita Ayalde from January 1961 to March 1979.

The pivotal issue to be resolved in this petition is whether

or not an agricultural laborer who was hired on pakyaw

basis can be considered an employee entitled to compulsory

coverage and corresponding benefits under the Social Security

Law.

Petitioner, Social Security System, argues that the

deceased Ignacio Tana, Sr., who was hired by Conchita Ayalde

on pakyaw basis to perform specific tasks in her sugarcane

plantations, should be considered an employee.

The Court of Appeals, however, ruled otherwise, reversing

the ruling of the Social Security Commission and declaring

that the late Ignacio Tana, Sr. was an independent contractor,

and in the absence of an employer-employee relationship

between Tana and Ayalde, the latter cannot be compelled to

pay to his heirs the burial and pension benefits under the SS

Law.

Supreme Court:

The mandatory coverage under the SSS Law (Republic Act No. 1161, as amended by

PD 1202 and PD 1636) is premised on the existence of an employer-employee relationship,

and Section 8(d) defines an employee as any person who performs services for an

employer in which either or both mental and physical efforts are used and who receives

compensation for such services where there is an employer-employee relationship. The

essential elements of an employer-employee relationship are: (a) the selection and

engagement of the employee; (b) the payment of wages; (c) the power of dismissal; and

(d) the power of control with regard to the means and methods by which the work is to

be accomplished, with the power of control being the most determinative factor.

There is no question that Tana was selected and his services engaged by either Ayalde

herself, or by Antero Maghari, her overseer. Corollarily, they also held the prerogative of

dismissing or terminating Tanas employment. The dispute is in the question of payment

of wages. Claimant Margarita Tana and her corroborating witnesses testified that her

husband was paid daily wages per quincena as well as on pakyaw basis. Ayalde, on the

other hand, insists that Tana was paid solely on pakyaw basis. To support her claim, she

presented payrolls covering the period January of 1974 to January of 1976;

and November

of 1978 to May of 1979.

A careful perusal of the records readily show that the exhibits

offered are not complete, and are but a mere sampling of

payrolls. While the names of the supposed laborers appear therein,

their signatures are nowhere to be found. And while they cover the

years 1975, 1976 and portions of 1978 and 1979, they do not cover the

18-year period during which Tana was supposed to have worked in

Ayaldes plantations.

These documents are not only sadly lacking, they are also

unworthy of credence.

In contrast to Ayaldes evidence, or lack thereof, is Margarita Tanas

positive testimony, corroborated by two (2) other witnesses. These

witnesses did not waver in their assertion that while Tana was hired by

Ayalde as an arador on pakyaw basis, he was also paid a daily

wage which Ayaldes overseer disbursed every fifteen (15) days. It is

also undisputed that they were made to acknowledge receipt of their

wages by signing on sheets of ruled paper, which are different from

those presented by Ayalde as documentary evidence.

Petitioners further argue that complainant miserably failed to

present any documentary evidence to prove his employment. There

was no timesheet, pay slip and/or payroll/cash voucher to speak

of. Absence of these material documents are necessarily fatal to

complainants cause.

No particular form of evidence is required to prove the existence

of an employer-employee relationship. Any competent and relevant

evidence to prove the relationship may be admitted. For, if only

documentary evidence would be required to show that relationship,

no scheming employer would ever be brought before the bar of

justice, as no employer would wish to come out with any trace of the

illegality he has authored considering that it should take much

weightier proof to invalidate a written instrument.

The argument is raised that Tana is an independenent contractor

because he was hired and paid wages on pakyaw basis. SC finds this

assertion to be specious for several reasons.

First, while Tana was sometimes hired as an arador or

plower for intermittent periods, he was hired to do other

tasks in Ayaldes plantations. It is indubitable, therefore, that

Tana worked continuously for Ayalde, not only as arador on

pakyaw basis, but as a regular farmhand, doing

backbreaking jobs for Ayaldes business. There is no shred of

evidence to show that Tana was only a seasonal worker, much

less a migrant worker. All witnesses, including Ayalde herself,

testified that Tana and his family resided in the plantation. If

he was a mere pakyaw worker or independent contractor,

then there would be no reason for Ayalde to allow them to

live inside her property for free. The only logical explanation

is that he was working for most part of the year exclusively for

Ayalde, in return for which the latter gratuitously allowed

Tana and his family to reside in her property.

Secondly, Ayalde made much ado of her claim that Tana could not be her

employee because she exercised no control over his work hours and method of

performing his task as arador. It is also an admitted fact that Tana, Jr. used his

own carabao and tools. Thus, she contends that, applying the control test, Tana

was not an employee but an independent contractor.

Be that as it may, the power of control refers merely to the existence of the

power. It is not essential for the employer to actually supervise the performance

of duties of the employee; it is sufficient that the former has a right to wield the

power.

Certainly, Ayalde, on her own or through her overseer, wielded the power

to hire or dismiss, to check on the work, be it in progress or quality, of the

laborers. As the owner/lessee of the plantations, she possessed the power to

control everyone working therein and everything taking place therein.

When a worker possesses some attributes of an employee and others of an

independent contractor, which make him fall within an intermediate area, he may

be classified under the category of an employee when the economic facts of the

relations make it more nearly one of employment than one of independent

business enterprise with respect to the ends sought to be accomplished.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

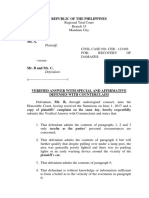

- Republic of The Philippines Municipal Trial CourtDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Municipal Trial CourtAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Municipal Trial CourtDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Municipal Trial CourtAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Organizational BehaviorDocument45 pagesChapter 5 Organizational BehaviorBashar Abu Hijleh100% (4)

- UST Golden Notes - Evidence PDFDocument78 pagesUST Golden Notes - Evidence PDFDr Bondoc100% (2)

- Articles About StressDocument15 pagesArticles About StressAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- SAMPLE Complaint For DamagesDocument8 pagesSAMPLE Complaint For DamagesAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Sample AnswerDocument6 pagesSample AnswerAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Benefits Under 11861Document81 pagesBenefits Under 11861Daisy Palero Tibayan100% (1)

- Lizatin Vs CamposDocument3 pagesLizatin Vs CamposAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- 2020-2023 CTA and ATU Local 241/308 Wages and Working Conditions Agreement (Contract)Document500 pages2020-2023 CTA and ATU Local 241/308 Wages and Working Conditions Agreement (Contract)Chicago Transit Justice Coalition100% (3)

- Physiotherapy For ChildrenDocument2 pagesPhysiotherapy For ChildrenSuleiman AbdallahNo ratings yet

- Rule 69 Garingan Vs GaringanDocument3 pagesRule 69 Garingan Vs GaringanAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Nebosh IGC 3Document18 pagesNebosh IGC 3kishoryawaleNo ratings yet

- 1.1 - Principles of Management & 1.2 Organisational BehaviourDocument331 pages1.1 - Principles of Management & 1.2 Organisational BehaviourArun Prakash100% (1)

- Training and DevelopmentDocument27 pagesTraining and Developmentghoshsubhankar1844No ratings yet

- Employee Motivation and PerformanceDocument93 pagesEmployee Motivation and PerformanceVictor Arul100% (5)

- Vda. de Manalo vs. CaDocument2 pagesVda. de Manalo vs. CaAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Trade, Investment & Econ Cooperation China-ASEAN: Case Study on MalaysiaDocument41 pagesTrade, Investment & Econ Cooperation China-ASEAN: Case Study on MalaysiaLdynJfr100% (1)

- #17 Case DigestDocument3 pages#17 Case DigestSerafina Suzy SakaiNo ratings yet

- Paguio Vs PLDTDocument2 pagesPaguio Vs PLDTAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- ProvRem CasesDocument122 pagesProvRem CasesAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- 1 MESINA Vs IACDocument3 pages1 MESINA Vs IACAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Philippines PLDT affidavit transferDocument2 pagesPhilippines PLDT affidavit transferAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Torts DamagesDocument37 pagesCase Digests Torts DamagesAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Memorandum Agreement Settlement DebtDocument2 pagesMemorandum Agreement Settlement DebtAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Campsite Resetting VillagersDocument5 pagesCampsite Resetting VillagersAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss - PawnshopDocument1 pageAffidavit of Loss - PawnshopAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- DigestDocument11 pagesDigestAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Letter RequestDocument1 pageLetter RequestAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss ID SampleDocument1 pageAffidavit of Loss ID SampleAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- 5 Davao Light vs. CADocument14 pages5 Davao Light vs. CAAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- RemLaw 2 NotesDocument1 pageRemLaw 2 NotesAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- 9 Perla Compania vs. Ramolete PDFDocument9 pages9 Perla Compania vs. Ramolete PDFAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- 10 Uy Jr. Vs CADocument9 pages10 Uy Jr. Vs CAAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Excused/Dispensed With: How To Enforce LiabilityDocument3 pagesExcused/Dispensed With: How To Enforce LiabilityAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Magna Carta For Micro, Smal and Medium Enterprises: Provided (A) in No Event Shall Title ToDocument3 pagesMagna Carta For Micro, Smal and Medium Enterprises: Provided (A) in No Event Shall Title ToAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Fermi's Paradox - Stephen WebbDocument5 pagesFermi's Paradox - Stephen WebbDesmawan AlfiantoNo ratings yet

- Cases Compilation LABORDocument23 pagesCases Compilation LABORAlexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Case Digests Pledge and REM For 09.07.2015Document33 pagesCase Digests Pledge and REM For 09.07.2015Alexandra Nicole Manigos BaringNo ratings yet

- Tax 2 Questions and AnswersDocument13 pagesTax 2 Questions and AnswersAlexandra Nicole Manigos Baring100% (1)

- Court rules on dismissal caseDocument13 pagesCourt rules on dismissal caseJanine OlivaNo ratings yet

- PROF JONA Casey Fink Nurse Retention ArticleDocument9 pagesPROF JONA Casey Fink Nurse Retention ArticleMaryam Teodosio Al JedawyNo ratings yet

- Offer Letter Sr Account ManagerDocument2 pagesOffer Letter Sr Account ManagerVikas Kumar PandeyNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 The Value of Work Employees ResponsibilitiesDocument39 pagesTopic 5 The Value of Work Employees Responsibilitiesnazlia880% (1)

- CV Advice Clinic2Document1 pageCV Advice Clinic2Mohi Ud Din AnwarNo ratings yet

- ESICDocument24 pagesESICIsha Sushil Bhambi100% (1)

- Hiring The Right PeopleDocument7 pagesHiring The Right PeopleGopi KrishnaNo ratings yet

- SITXGLC001 - Research and Comply To Regulatory Requirements WorksheetDocument3 pagesSITXGLC001 - Research and Comply To Regulatory Requirements Worksheetosama najmi0% (1)

- Member's Data Form for Gian Carlo ApostolDocument2 pagesMember's Data Form for Gian Carlo ApostolHershey GabiNo ratings yet

- Business Studies Class 12 Revision Notes Chapter 1 Nature Significance ManagementDocument3 pagesBusiness Studies Class 12 Revision Notes Chapter 1 Nature Significance ManagementTarun BhattNo ratings yet

- Whs Bullying and Harassment PolicyDocument2 pagesWhs Bullying and Harassment PolicySaverioNo ratings yet

- Layoffs, Outsourcing, Offshoring Impact Employee ReactionsDocument11 pagesLayoffs, Outsourcing, Offshoring Impact Employee Reactionsfawadn_84No ratings yet

- ACNT Diploma of Remedial MassageDocument9 pagesACNT Diploma of Remedial MassageagatajazzNo ratings yet

- Dheeraj 1Document1 pageDheeraj 1MOHD ASRAF ANSARINo ratings yet

- Employees' Provident Fund and Miscellaneous ActDocument20 pagesEmployees' Provident Fund and Miscellaneous ActAnchal PundirNo ratings yet

- Restaurant Accounting With Quic - Doug Sleeter-4Document21 pagesRestaurant Accounting With Quic - Doug Sleeter-4ADELALHTBANINo ratings yet

- HR407 en Col94 CanadaDocument549 pagesHR407 en Col94 CanadaVamsi SuriNo ratings yet

- GAP Analysis - IWAY 6 0 FinalDocument16 pagesGAP Analysis - IWAY 6 0 FinalSan ThisaNo ratings yet

- Labor Agreement between Encore Event Technologies and IATSE Local 720Document40 pagesLabor Agreement between Encore Event Technologies and IATSE Local 720lvstagehandNo ratings yet

- Five J Taxi Vs NLRCDocument6 pagesFive J Taxi Vs NLRCDaley CatugdaNo ratings yet