Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Air Traffic Control

Uploaded by

Datta MksOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Air Traffic Control

Uploaded by

Datta MksCopyright:

Available Formats

Air traffic control (ATC) is a service provided by

ground-based controllers who direct aircraft on the ground and in the air. The primary purpose of ATC systems worldwide is to separate aircraft to prevent collisions, to organize and expedite the flow of traffic, and to provide information and other support for pilots when able

In many countries, ATC services are provided throughout

the majority of airspace, and its services are available to all users (private, military, and commercial). When controllers are responsible for separating some or all aircraft, such airspace is called "controlled airspace" in contrast to "uncontrolled airspace" where aircraft may fly without the use of the air traffic control system. Depending on the type of flight and the class of airspace, ATC may issue instructions that pilots are required to follow, or merely flight information (in some countries known as advisories) to assist pilots operating in the airspace. In all cases, however, the pilot in command has final responsibility for the safety of the flight, and may deviate from ATC instructions in an emergency.

The primary method of

controlling the immediate airport environment is visual observation from the airport traffic control tower (ATCT). The ATCT is a tall, windowed structure located on the airport grounds. Aerodrome or Tower controllers are responsible for the separation and efficient movement of aircraft and vehicles operating on the taxiways and runways of the airport itself, and aircraft in the air near the airport, generally 5 to 10 nautical miles (9 to 18 km) depending on the airport procedures

Ground Control is responsible for the

airport "movement" areas, as well as areas not released to the airlines or other users. This generally includes all taxiways, inactive runways, holding areas, and some transitional aprons or intersections where aircraft arrive, having vacated the runway or departure gate. Exact areas and control responsibilities are clearly defined in local documents and agreements at each airport. Any aircraft, vehicle, or person walking or working in these areas is required to have clearance from Ground Control.

Local Control (known to pilots as

"Tower" or "Tower Control") is responsible for the active runway surfaces. Local Control clears aircraft for takeoff or landing, ensuring that prescribed runway separation will exist at all times. If Local Control detects any unsafe condition, a landing aircraft may be told to "go-around" and be re-sequenced into the landing pattern by the approach or terminal area controller.

Clearance Delivery is the position

that issues route clearances to aircraft, typically before they commence taxiing. These contain details of the route that the aircraft is expected to fly after departure. Clearance Delivery or, at busy airports, the Traffic Management Coordinator (TMC) will, if necessary, coordinate with the en route center and national command center or flow control to obtain releases for aircraft

Many airports have a radar control

facility that is associated with the airport. In most countries, this is referred to as Terminal Control; A Terminal Radar Approach Control (or TRACON) is an air traffic control facility usually located within the vicinity of a large airport. Typically, the TRACON controls aircraft within a 20-50 nautical mile (37 to 93 km) radius of the major airport and a number of "satellite airports" between surface and 1,200 feet (370 m) up to between 10,000 feet (3,000 m) and 23,000 feet (7,000 m). A TRACON is sometimes called Approach Control or Departure Control in radio transmissions

The day-to-day problems faced by the air

traffic control system are primarily related to the volume of air traffic demand placed on the system and weather. Several factors dictate the amount of traffic that can land at an airport in a given amount of time. Each landing aircraft must touch down, slow, and exit the runway before the next crosses the approach end of the runway. This process requires at least one and up to four minutes for each aircraft. Allowing for departures between arrivals, each runway can thus handle about 30 arrivals per hour. A large airport with two arrival runways can handle about 60 arrivals per hour in good weather.

Problems begin when airlines schedule more arrivals into

an airport than can be physically handled, or when delays elsewhere cause groups of aircraft that would otherwise be separated in time to arrive simultaneously. Aircraft must then be delayed in the air by holding over specified locations until they may be safely sequenced to the runway. Up until the 1990s, holding, which has significant environmental and cost implications, was a routine occurrence at many airports. Advances in computers now allow the sequencing of planes hours in advance. Thus, planes may be delayed before they even take off (by being given a "slot"), or may reduce speed in flight and proceed more slowly thus significantly reducing the amount of holding

By PRANEETH

You might also like

- AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL (A Summary)Document11 pagesAIR TRAFFIC CONTROL (A Summary)Prinkesh BarodiyaNo ratings yet

- AirportDocument18 pagesAirportRufaidaNo ratings yet

- ATC GUIDEDocument27 pagesATC GUIDEVinoth ParamananthamNo ratings yet

- Air Traffic ControlDocument24 pagesAir Traffic ControlPrabhakar Kumar Barnwal100% (1)

- Airport Components GuideDocument5 pagesAirport Components GuideAsif KhanNo ratings yet

- ATCDocument25 pagesATCVigneshVickeyNo ratings yet

- ATC Apr 10Document23 pagesATC Apr 10John MaclinsNo ratings yet

- Air Traffic Control Lecture-1Document37 pagesAir Traffic Control Lecture-1azhar ishaq100% (1)

- Air Traffic Control PhrasesDocument1 pageAir Traffic Control PhrasesronNo ratings yet

- NOTAM 101 Back To BasicsDocument48 pagesNOTAM 101 Back To BasicsJulio RaimondNo ratings yet

- ATC RADAR SYSTEMS GUIDEDocument18 pagesATC RADAR SYSTEMS GUIDEShubham BansalNo ratings yet

- Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA 2008) - Chapter 07Document26 pagesPilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA 2008) - Chapter 07Venn WyldeNo ratings yet

- Atc Clearances RMDocument53 pagesAtc Clearances RMRoel MendozaNo ratings yet

- Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM)Document27 pagesAir Traffic Flow Management (ATFM)Johari JeffreyNo ratings yet

- AtcDocument48 pagesAtcAhmed Abdoul Zaher100% (1)

- Virtual Pilot's Guide to Flight ChartsDocument36 pagesVirtual Pilot's Guide to Flight ChartsAndy KeeneyNo ratings yet

- Flight Management System (FMS)Document28 pagesFlight Management System (FMS)rasekakmNo ratings yet

- Atc PhraseologyDocument13 pagesAtc PhraseologyH89SA100% (1)

- Instrument Rating Handbook PDFDocument118 pagesInstrument Rating Handbook PDFAndrzej AndreNo ratings yet

- Automatic Landing SystemsDocument8 pagesAutomatic Landing SystemsKoustubh VadalkarNo ratings yet

- TP 3783 Air Carrier Inspector Manual TP3783EDocument104 pagesTP 3783 Air Carrier Inspector Manual TP3783EHarry NuryantoNo ratings yet

- TransponderDocument43 pagesTransponderNguyễn NhậtNo ratings yet

- Load Controller Safety ProceduresDocument11 pagesLoad Controller Safety ProceduresRamyAbdullahNo ratings yet

- Required Comms with ATC (39Document68 pagesRequired Comms with ATC (39dukekanaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Instrumentation Acronyms: and Reporting SystemDocument1 pageAdvanced Instrumentation Acronyms: and Reporting SystemAliCanÇalışkanNo ratings yet

- ATS Flight PlanDocument9 pagesATS Flight Planchhetribharat08No ratings yet

- Sid/star ScenarioDocument30 pagesSid/star ScenarioAmirAli MohebbiNo ratings yet

- Decode the NOTAM Code for Lighting FacilitiesDocument11 pagesDecode the NOTAM Code for Lighting FacilitiesRangga PratamaNo ratings yet

- Runway Safety Best Practices BrochureDocument25 pagesRunway Safety Best Practices BrochureMo AllNo ratings yet

- Airline Announcements - EnglishClubDocument3 pagesAirline Announcements - EnglishClubLionel YaminNo ratings yet

- A320 / A32Nx Flybywire: Beginner Guide - Checklist & Procedures For Ms Flight Simulator by Jaydee V0.8Document4 pagesA320 / A32Nx Flybywire: Beginner Guide - Checklist & Procedures For Ms Flight Simulator by Jaydee V0.8bink-simracingNo ratings yet

- Airspace Classification LNDocument47 pagesAirspace Classification LNM S PrasadNo ratings yet

- Copy IFR Clearances with Clearance ShorthandDocument1 pageCopy IFR Clearances with Clearance ShorthandA320viator100% (1)

- ICAO Abbr CodesDocument20 pagesICAO Abbr CodesJuan TamaniNo ratings yet

- Jeppesen MetDocument194 pagesJeppesen MetVasi Adrian100% (2)

- Aerodrome PDFDocument100 pagesAerodrome PDFAlizza Fabian Dagdag100% (1)

- IFR ChartsDocument4 pagesIFR Chartsc_s_wagonNo ratings yet

- ATA 46 - Air Traffic Control System - Basics PDFDocument18 pagesATA 46 - Air Traffic Control System - Basics PDFanilmathew244No ratings yet

- Aeroplane Performance - NPA25 - 032 ED03 110901Document179 pagesAeroplane Performance - NPA25 - 032 ED03 110901Don100% (1)

- CAP 413 Radio Telephony Supplement 1 A Quick Reference Guide To UK Radio Telephony Phraseology For Commercial Air Transport PilotsDocument16 pagesCAP 413 Radio Telephony Supplement 1 A Quick Reference Guide To UK Radio Telephony Phraseology For Commercial Air Transport PilotsXin ZhiNo ratings yet

- Avionics-Ae 2401: Unit - 1 Prepared by Rajarajeswari.M Mohammed Sathak Eng CollegeDocument129 pagesAvionics-Ae 2401: Unit - 1 Prepared by Rajarajeswari.M Mohammed Sathak Eng CollegeGaneshVijay0% (1)

- Lecture 7 - Global Positioning GpsDocument40 pagesLecture 7 - Global Positioning Gpszuliana100% (2)

- Topic 10 - FMS PDFDocument26 pagesTopic 10 - FMS PDFnjnvsrNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Flight Instruments and Navigation EquipmentDocument3 pagesAircraft Flight Instruments and Navigation EquipmentMike AguirreNo ratings yet

- ICAO Phraseology Quick ReferenceDocument20 pagesICAO Phraseology Quick ReferenceSebastián Fonseca OyarzúnNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 An 3Document42 pagesLecture 2 An 3Raluca StoicaNo ratings yet

- CNSATM Presentation For Air Traffic Control OfficersDocument61 pagesCNSATM Presentation For Air Traffic Control OfficersZulfiqar Mirani100% (4)

- Maintenance Training at Delta 2013Document26 pagesMaintenance Training at Delta 2013Abu Bakar SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Guidance on Processing and Displaying ADS-B Data for Air Traffic ControllersDocument15 pagesGuidance on Processing and Displaying ADS-B Data for Air Traffic ControllersĐỗ Hoàng An100% (1)

- RNP 2Document143 pagesRNP 2eak_ya5875No ratings yet

- Air Traffic ControlDocument27 pagesAir Traffic ControlSumit V MenonNo ratings yet

- ATC Handbook (Jan2012)Document46 pagesATC Handbook (Jan2012)Muhammad Angger Pamungkas67% (3)

- Air Crash Investigations - Loss of Cargo Door - The Near Crash of United Airlines Flight 811From EverandAir Crash Investigations - Loss of Cargo Door - The Near Crash of United Airlines Flight 811No ratings yet

- Air Traffic ControlDocument24 pagesAir Traffic ControlAli HassanNo ratings yet

- Airport Control MMMMMDocument18 pagesAirport Control MMMMMSatish ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- ATC BasicsDocument10 pagesATC BasicsChristine CandareNo ratings yet

- Components of The Aviation Infrastructure - Airport Terminal BuildingsDocument8 pagesComponents of The Aviation Infrastructure - Airport Terminal BuildingsJackielou Marmojada DomaelNo ratings yet

- Fly Dubai TimetableDocument15 pagesFly Dubai TimetableEvgeny KirovNo ratings yet

- KTW MirDocument57 pagesKTW MirAwiatorzy WielcyNo ratings yet

- SBBVDocument10 pagesSBBVFERNANDO TORQUATO LEITENo ratings yet

- ATC Flight PlanDocument21 pagesATC Flight PlanKabanosNo ratings yet

- ET575 Flight Plan from Chicago to Addis AbabaDocument120 pagesET575 Flight Plan from Chicago to Addis AbabaAbraham TesfayNo ratings yet

- CiricDocument6 pagesCiricapi-448672602No ratings yet

- VVCT Terminal Charts and Arrival ProceduresDocument12 pagesVVCT Terminal Charts and Arrival ProceduresNguyen MinhNo ratings yet

- Promulgation of GRF information through SNOWTAM and ATISDocument62 pagesPromulgation of GRF information through SNOWTAM and ATISAliNo ratings yet

- LECU (Cuatro Vientos) : General InfoDocument6 pagesLECU (Cuatro Vientos) : General InfoMiguel Angel MartinNo ratings yet

- PPL OpDocument122 pagesPPL OpBea AlduezaNo ratings yet

- DGAADocument28 pagesDGAAYusuf UsmanNo ratings yet

- Cartas ANTONIO MACEO INTL City SANTIAGO DE CUBAMUCUDocument16 pagesCartas ANTONIO MACEO INTL City SANTIAGO DE CUBAMUCUREGINO MARCANONo ratings yet

- Jeppview For Windows: List of Pages in This Trip KitDocument15 pagesJeppview For Windows: List of Pages in This Trip Kitagagahg221No ratings yet

- TQPF/AXA - Lloyd Intl Airport Approach ChartDocument2 pagesTQPF/AXA - Lloyd Intl Airport Approach Chartjuan romeroNo ratings yet

- FAA & ICAO - Differences 11Document1 pageFAA & ICAO - Differences 11hq bNo ratings yet

- LLBGLCLK PDF 1573479694Document21 pagesLLBGLCLK PDF 1573479694Royal ArtzNo ratings yet

- Cyvreddf PDF 1514803401Document75 pagesCyvreddf PDF 1514803401bittekeinspam123No ratings yet

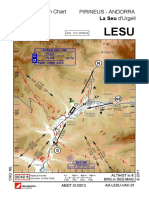

- Visual Approach Chart Pirineus - Andorra: La Seu D'urgellDocument5 pagesVisual Approach Chart Pirineus - Andorra: La Seu D'urgellNight LightNo ratings yet

- Cape Town INTL Area Airspace HotspotDocument1 pageCape Town INTL Area Airspace HotspotMohamed Anas SayedNo ratings yet

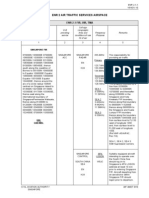

- Enr 2 Air Traffic Services AirspaceDocument10 pagesEnr 2 Air Traffic Services AirspaceMuhammad Fikri B SamsudinNo ratings yet

- APPROACHDocument9 pagesAPPROACHCatalin CiocarlanNo ratings yet

- Leap PDFDocument5 pagesLeap PDFMiguel Angel MartinNo ratings yet

- Atp - (Chap. 06) Flight OperationsDocument22 pagesAtp - (Chap. 06) Flight Operationscorina vargas cocaNo ratings yet

- AIP SUPPLEMENT ISSUED FOR VARANASI ILS CHARTDocument2 pagesAIP SUPPLEMENT ISSUED FOR VARANASI ILS CHART294rahulNo ratings yet

- W6 8305/18 JUL/FCO-LMP: - Not For Real World NavigationDocument40 pagesW6 8305/18 JUL/FCO-LMP: - Not For Real World NavigationDejw AmbroNo ratings yet

- Reported Speech PracticeDocument2 pagesReported Speech PracticeGeorge RoaNo ratings yet

- Cap 637Document105 pagesCap 637Tino 747No ratings yet

- Visual Approach Chart - Icao BUSAN/Gimhae: JinyeongDocument1 pageVisual Approach Chart - Icao BUSAN/Gimhae: Jinyeong한울 HANULENo ratings yet

- Asturias - LEASDocument32 pagesAsturias - LEASRafael GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- TSN Airport Information and Arrival/Departure ProceduresDocument25 pagesTSN Airport Information and Arrival/Departure Proceduresdranreb1990No ratings yet